Courtesy of Dan Daley via SVG

Mixing hundreds of audio elements creates a virtual crowd that makes the game sound real

Perhaps no sport lives and dies by the intensity of its crowd reactions as much as basketball. With triple-digit game scores as close as a single point with tenths of a second left on the clock, crowd reactions can literally influence the outcome of games. That fact confronted the folks figuring out how to re-create the sounds and swells of those crowds when the NBA began its COVID-shortened and crowd-less season in late July, within a protective bubble inside the Wide World of Sports venues (WWoS) at Disney World.

“The goal was to replicate what the players would hear if there were 18,000 people around them in an arena,” says Carlton Myers, Associate VP, live production and entertainment, NBA Entertainment. “A 360-degree soundscape where the sound would come from all directions, and it would sound different for home and visitors and for each shot.”

It was a tall order, and it produced a startlingly realistic sonic environment that authentically re-creates what NBA players experience on the courts, doing so with a technology infrastructure unlike any ever seen.

The league worked with Firehouse Productions, the integrator hired to install and operate the audio systems within the NBA bubble. Led by Kevin Dobstaff, production supervisor, live broadcast venues, Emerald City/NBA Restart, Emerald City Productions was the technical production supervisor on the entire project and worked on all areas of the production.

The Crowd PA

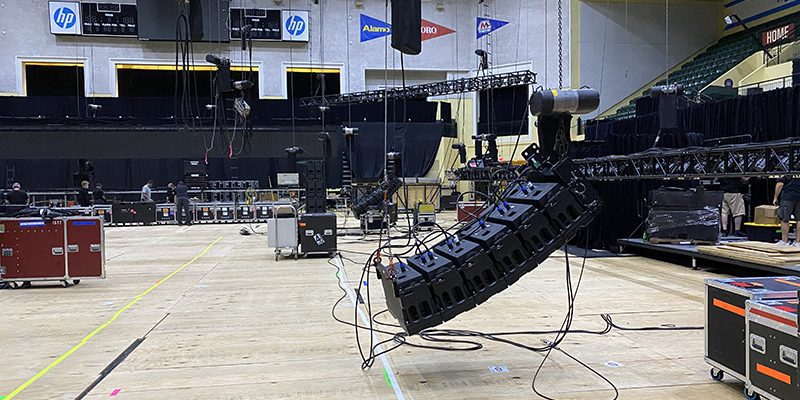

Sound is focused on each of the three WWoS courts, each with distinct system designs. The PA system in The Arena, the main national-telecast court and site of Conference Finals and NBA Finals, is unique in that it puts the sound only on the field of play. It comprises 60 L-Acoustics K2 loudspeakers configured as 10 hangs of six boxes each, buttressed by a dozen L-Acoustics KS28 subs. These speaker clusters place the sound on the court instead of the seats (which are “occupied” by 300+ actual fans populating 17-ft. LED videoboards lining the sides of the court via Microsoft Teams’ Together mode; the audio, along with venue announcers and a DJ, is also part of the ultimate mix). It’s all mixed through a DiGiCo SD7 console — heavily loaded at 147 inputs — by the front-of-house A1.

The HP Field House court, used for the regular season to second round, and Visa Athletic Center, for games broadcast exclusively by regional sports networks, have DiGiCo and Yamaha mix consoles and two PA systems each — one for the court, one for the stands — comprising combinations of L-Acoustics and JBL components.

Who’s Who in the Virtual ‘Crowd’

However, it’s the content of the crowd audio, and how it comes together, that’s especially remarkable. More than 700 individual audio clips — cheers, boos, and other reaction sounds — are stored on media servers and controlled over a Figure 53 QLab audio interface. According to Myers, these clips have been collected from a variety of authentic sources, including videogame publisher 2K Sports’ NBA 2K series, as well as from recordings of actual games, provided by the teams and the league. In addition, Firehouse Productions provides audio recorded at recent NBA All-Star Games, for which Firehouse also handles some venue and broadcast services.

“We collected actual audio chants and cheers from all 22 teams,” Myers explains. “We asked them to send us sound that was specific to them, to make them feel at home here.”

Examples include Miami Heat announcer Michael Baiamonte’s trademark “Dos minutos!” warning as the game clock ticks down and the Portland Trail Blazers’ comeback call “Dame Time!” for superstar Damian Lillard.

These and hundreds of other audio clips sit atop an ambient bed of “murmur” tracks, a concatenation of hundreds of indistinguishable voices also culled from NBA-related sources. These form the foundation for individual fan and crowd sounds controlled by two “sound sweeteners”— audio mixers with broadcast and other professional CVs — per game via the QLab interface. Each interface offers separate, virtual activation buttons for dozens of individual sound clips, and each channel that these team-specific clips are assigned to has five intensity levels that the mixers can choose based on the heat of the moment during play; the murmur tracks have nine intensity levels and will continuously ebb and flow with the game’s narrative like the underscore to a film. There’s yet another step as well: the interface is programmed to “randomize” the sounds, so that no single clip is played over again.

There’s still one more level of audio. The “game director 2” — actually, the team’s game director when they aren’t sitting at the scorers’ table and working in that capacity — joins the sound sweeteners and calls up an additional layer of sound effects, using an iPad, for specific moments in a game, such as boos on questionable calls and groans for near-miss shots.

“Those are available to enhance the impactful moments,” says Myers.

Practice Shots

Not surprisingly, the four two-person teams that serve as sound sweeteners and the nine game directors spent a considerable amount of time in rehearsal for their task, practicing to video of NBA games to get not just the rhythm of the game but also the nuances of individual teams and their fans.

“For instance, when the home team is down by 10, they run up and tie the game, and the visitors call a timeout,” says Myers. “The home fans will go crazy! [The sweeteners] have to understand nuances like momentum.”

Some of this took place starting in April, in a rented barn venue at the Taconic Retreat in Upstate New York, near Firehouse Productions’ HQ in the town of Red Hook. There, the entire sound system and its playout components were set up, initially as a proof of concept for the idea, developed by Firehouse Productions VP Mark Dittmar, and then to familiarize the mixers with managing this new universe of sound.

All of this is pumped through PA systems designed to create zones around the venues that allow the crowd-sound mixers to put different elements in different areas of the venue at different times and volume levels, to approximate the locations of home and away fans’ responses.

The workflow for this complex audio infrastructure was fine-tuned with input from the players themselves. During the scrimmage games in July before the start of the season, team members and representatives were polled about the sounds, and the overall response was positive, Meyer says.

“A few told us they wanted it louder,” he says, noting a common reaction. “We took that to heart. We had been apprehensive that we were doing too much, but they wanted more of it.”

Myers adds that, once the audio mixers had gotten through the first week of the season, they were comfortable in what is certainly a unique audio environment in sports broadcasting.

“We’re trying to replicate the intensity and the anticipation that the players feel during a game in a full arena,” he says. “That’s not easy. But we’re succeeding.”